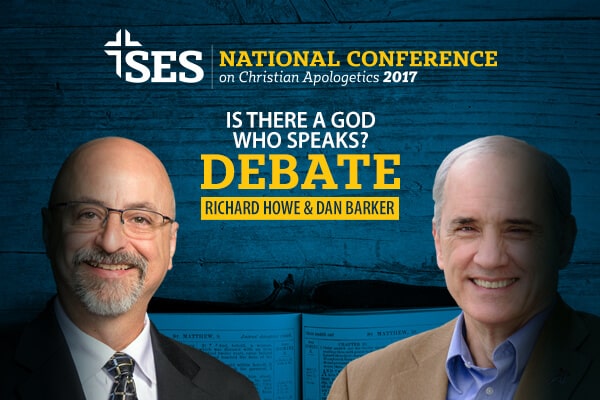

This year’s SES National Conference on Christian Apologetics will feature a live debate between SES Emeritus Professor of Philosophy and Apologetics, Dr. Richard Howe, and former professing Christian, pastor, and worship leader, Dan Barker. Mr. Barker is the current co-president of the Freedom from Religion Foundation. Dr. Howe and Mr. Barker will be debating the question, “Is there a God who speaks?” The debate is included in the conference ticket price.

We recently interviewed Dr. Howe as he prepares for his interaction with Mr. Barker.

SES: Why would a Christian conference give stage time to an atheist?

Dr. Howe: I’m thinking of this from several angles. One, I think it gives us a certain amount of credibility with the general public —that we’re willing to not shut down the opposing voices. Especially in today’s climate, where you see so many instances of free speech being violently shut down. It’s all the more important that we Christians, and as thinking human beings, display this attitude: that, in principle, we’re willing to take on any opposing idea in order for the market place of ideas to be the arena where these things are settled, rather than government legislation. As Americans, we cherish the arena of ideas politically, but I think we also need to remember that we cherish it as Americans religiously. Atheism is a new phenomenon relatively speaking. That is, it’s becoming more and more socially acceptable to declare one’s atheism publicly. So rather than wanting to preempt the debate by some other kind of means, we go, “No. We’re not afraid to have an open, fair discussion as long as we all agree on the rules of logic and reason.” I think that’s a good thing in principle.

Now, some of our regular attendees may worry more specifically about why we would take time at the National Conference on Christian Apologetics to debate an atheist. In response to these individuals, we can always appeal to the open attitude we attempt to portray to the general public, but more than that, it also shows that despite the belligerence that is often displayed by both sides of this debate, we at SES are willing to show people how to have these conversations in a chartable and cordial way.

Third, debates are practical and efficient events. They help people hear the best arguments and best responses, as well as inform audiences about arguments they may have never heard. Furthermore, you’ve got people out there in the audience who may actually be struggling with some of the same questions that Dan may bring up in the debate. On a personal note, during my days as a young Christian, it was debates like the one we are hosting at the National Conference that helped me come to grips with the truth of Christianity. So, I’m convinced that some of the best things that can happen to people who attend our conference is to see two people who take these issues very seriously, debate the issue and be held accountable before their fellow man in terms of their logic and reason. That can’t help but be a good thing.

Fourth, it also provides a great opportunity for people to discover new resources. That is, they hear things vetted, they don’t necessarily settle everything in a two or three hour encounter, but horizons are expanded. People discover new resources, “Hey, he quoted this book” or, “He mentioned this thinker. Now I can take the discussion on privately in my own research.” I think it helps expand people’s horizons intellectually.

SES: Why do you think doing debates is important for Christian apologetics?

Dr. Howe: First, I’d like to answer this question broadly, and then more specifically. Broadly speaking, one of the most common criticisms that I’ve encountered with people when they’re thinking or hear about a debate coming up is, “Have you ever seen your opponent change his mind?” And my answer is, “Well, no.” To which you would think they would probably ask, “Then why do you do it?” I remind them, the reason we do debates, at least initially, is not to change the other guy’s mind. It’s to address the people in the audience; the debate is for the audience, not the debate participants. So as I’m debating Dan Barker, I pray that he reconsiders his position, but my aim is not to change Dan’s mind. My primary aim is to change the mind of people out in the audience who may not be as embedded in their atheism as he has become. I mean, I certainly would love to see him change his mind and fall on his knees right there and repent, but I’m sure he’s not expecting me to become an atheist during the debate.

But more specifically, one of the syndromes that’s always a danger for a school like SES is becoming comfortable learning apologetics arguments and their conclusions in isolation. In the context of seminary education, people are often learning these arguments with others who already grant their conclusions. But when students or congregants like this go out into the marketplace of ideas where their knowledge will be confronted, they realize defending their faith is a little more difficult than they thought. So, what we learned at SES was, no, we need to provide our students with as many opportunities to directly encounter the opposing points of view as possible.

Within the context of a seminary curriculum, we can do this in two ways. One way is to read sources from opposing points of view. For example, at SES I teach a class on contemporary atheism. In that class, my students read the sources written by contemporary atheists. Secondly, how do you otherwise confront, in the context of an apologetics conference, the opposing points of view? Well, you invite someone to debate. Invite a Dan Barker to dispute the existence of God, and you have created a forum with accountability for both parties involved. I’m not going to be allowed to get away with tricks and ignore data and arguments when I debate Dan because he’s not going to let me. He has an interest in making sure I’m held accountable to the arguments and evidence.

SES: In Dan Barker’s book Godless, he admits that much of his Christian identity and belief was based on personal experience. Many Christians likely find themselves in the same place. Is this a healthy way to judge the truth claims of Christianity or anything else for that matter?

Dr. Howe: This is a very important question because, for one thing, the word “experience,” particularly in the context of disputes about theology and other issues, can mean something very different than say, what the word “experience” may mean in the context of a philosophical discussion. Typically, when a person talks about their experience in the context of religious views, they are referring to the subjective. For instance, a certain feeling they have that they interpret as God speaking to them or God confirming something. You know the burning in the bosom the Mormon has, or “being led” the way a lot of evangelicals talk. So that’s one use of the term “experience.” In that regard, I think it’s a very unstable and unreliable way of settling theological disputes. You don’t find that in the Scriptures. For example, the epistles to the churches don’t instruct the saints to judge truth by means of some subjective experience. “I felt like the Lord was really laying this on my heart.” You don’t find that kind of language in the New Testament for the church. Instead you find, “Believe not every spirit, but test the spirits.” Paul says, “whatsoever things are true,” that’s the very first thing in the list in Philippians, “think on these things.” There, truth is objective. In Romans Paul tells us about two groups: one we are to receive (Rm. 14), and the other we are to avoid (Rm. 16). When you look at the inverse parallels between those two, the ones that are received are weak in the faith. You receive them, but don’t dispute with them over questionable issues. But in Romans 16, the ones he said to avoid are those who cause divisions contrary to the doctrines which they had received. Well, there it makes it objective. It’s doctrine that we have received, and I would argue, it came from the Apostles. Right there, even in the theological, we’ve got to get away from the subjective.

Having said that then, for better or worse, philosophers can use the same word “experience.” There, I would say, in the philosophical sense all knowledge begins in experience. But there, I don’t mean a subjective feeling like a wooing from the Lord, confirmation, or a peace. There, what I mean is empirical experience. What I see, hear, taste, touch, or smell. I would argue, as a classical realist and Aristotelian Thomist, that all knowledge begins there, though it doesn’t end there. So the problem with someone like a Richard Dawkins, for example, is that they may grant that knowledge begins in experience, but they also try to argue that it also ends in experience. They don’t realize that’s impossible. There are things we know to be true that are beyond the physical realm, but we know them to be true because they arise out of our experience of the physical realm, that is, things like universals, natures, and causality.

So, in the typical way in which the word “experience” is used, I would say no, it’s not a good method of discerning what’s true or false. In the philosophical way in which a classical empiricist would use the word, I would say experience absolutely is where knowledge begins.

SES: What would you say to any skeptics who plan to attend the debate?

Dr. Howe: Come to the event and hear both sides, and continue the conversation. Come and learn of some new resources, perhaps. For some, they may learn of some new arguments on both sides. If you disagree with the argument, how would you answer it? If you agree with the argument, how would you defend it against objections. I think everybody wins at a human level just by the very activity of engaging in debate. Of course, I would say all this to the Christians as well.

You can learn more about the debate and all the details of the 2017 SES National Conference on Christian Apologetics by visiting http://conference.staging.ses.edu

Early bird pricing ends Aug. 1. In addition, among our other discounts for home school families and groups, we are offering a 50% discount for skeptics who wish to attend. Simply request the skeptic discount code by calling SES at (704) 847-5600 x201.